By William Deatherage

NOTICE: Thank you for your questions! A few have been answered following the article as of May 23, 2019! Future questions of note will be featured and updated.

The following article is based around Theoretical Applied Theology and should not be taken as dogmatic or doctrinal Church teaching. Its intention is to provoke thought by bringing in outside subject interests to interact with Theology.

Update November 10, 2019: Term “free will” as defined by this article has been amended to reflect a purely neurological perspective of free will, not a spiritual or ethical one.

The commandment of love is also the measure of the tasks and demands that have to be faced by all men -all persons and all communities- if the whole good contained in the acting and being “together with others” is to become a reality.”-Karol Wojyla, The Acting Person

Terms discussed:

- Bundle Theory: the idea that every material thing is built of smaller material things and composes larger material things

- Conscious: the part of our mind that realizes actions that are performed, which neuroscience has revealed is more dependent on the subconscious, not to be confused with conscience, which refers to the process of making decisions and is not a neurological concept

- Individual: a bundle of smaller units that compose what we call a person

- Free Will (Old Neurological Usage): the ability to make conscious choices.

- Free Will (New Neurological Usage): the ability to will our desires into reality without external interruption

- Self-Reflection: the act of contemplation without significant exterior influence

- Subconscious: the part of our brains that heavily influences decisions

Summary (TLDR) of this Article is Below if you scroll down all the way

Hello there and happy Summer! Traditionally, we at Clarifying Catholicism enjoy giving our writers some time off during this time of year. However, since I’ve been researching philosophy quite intensely lately, I figured it might be appropriate to share some of my thoughts and findings throughout the Summer. Keep in mind that most of these weekly posts will primarily draw upon philosophy, social science, and current events, but will circle back to theology towards the end.

Don’t worry. It might go out a few miles, but it’ll circle back around eventually.

Don’t worry. It might go out a few miles, but it’ll circle back around eventually.

What better way to start off this series than by talking about a prominent atheist? Particularly, I’d like to bring up Sam Harris, author of works such as The End of Faith and Free Will, the latter which I would like to address. In his controversial work, Harris asserts that free will is illusory, and that all of our decisions in life are based off chemicals and functions of our very materialistic minds. This is not a new idea, and I would like to draw attention to the merits of his argument, as they do hold some important truths that can be drawn from it. I feel like Christians are often turned away from recognizing the value of certain arguments on the basis that the person asserting such claims are antagonistic towards the faith. Let there be no mistaking: Harris does NOT like the Church. He detests religion. But this does not mean that all of his thoughts are unworthy of attention. After all, the philosophy of modern art stems from the writings of a Nazi sympathizer, though that is a subject for another day.

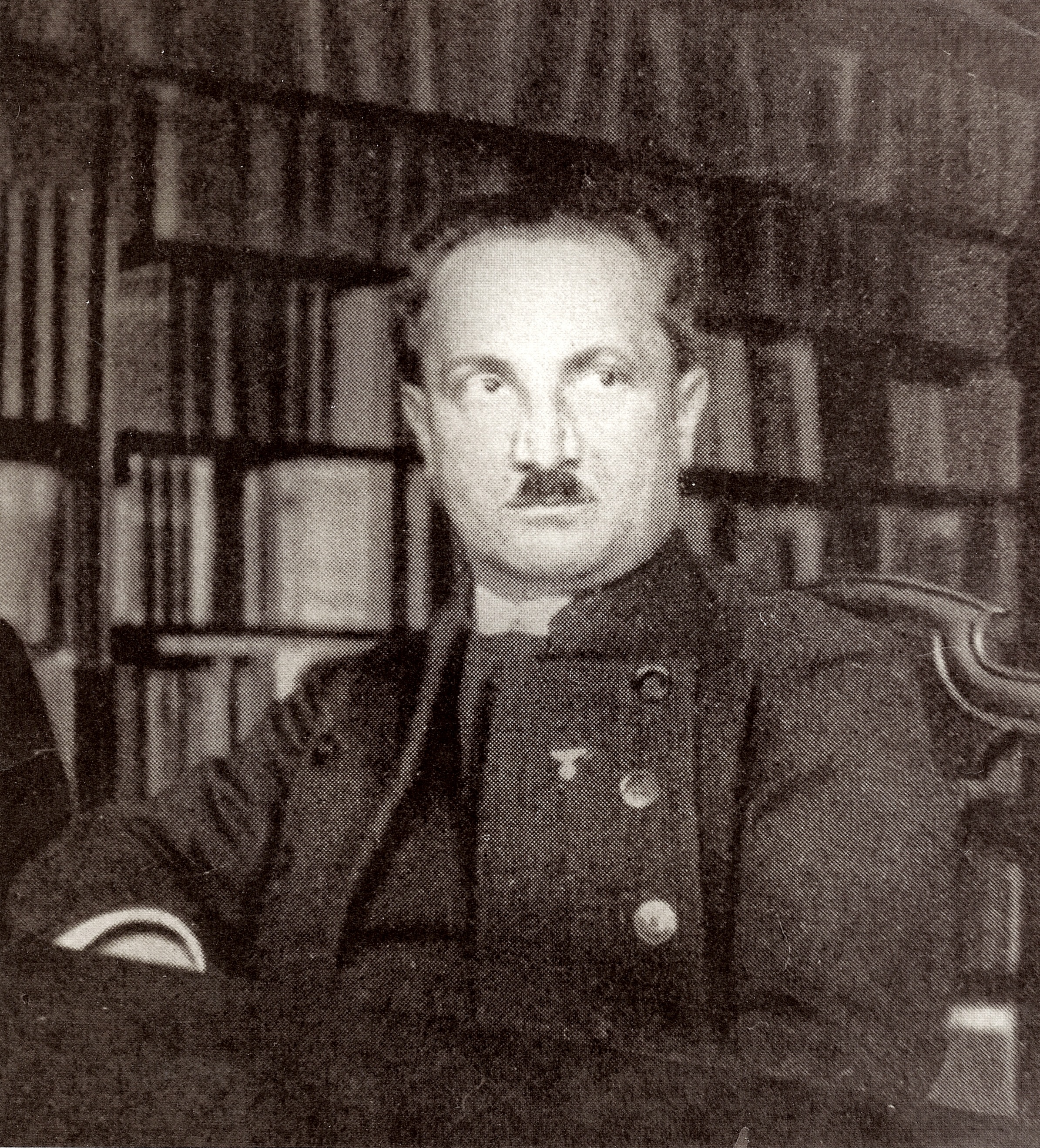

That mustache looks a little too familiar, but we’ll get into him next week.

That mustache looks a little too familiar, but we’ll get into him next week.

Individuality: A Social Psychological Construct

The basis of Harris’s argument harkens to a classical philosophical debate: is there something inside us (like a soul) that makes me me, or am I merely a bundle of ever-changing materials composed of chemicals? While most Christians I’ve talked to shudder at the concept of the second option, it is actually a point of view I’ve come to adopt over time. I see no problem with the idea that each person is a colorful assortment of cells and processes. This disregards the soul of course, but what I certainly disagree with is the idea that there exists a material constant that scientists just haven’t found. So, we’re bundles, but this isn’t a bad thing. If anything, our complexity draws me towards a greater appreciation of God’s craftsmanship.

Let’s look at Liam (Trustee of Clarifying Catholicism). So, Liam is just a bundle of materials, then what makes Liam Liam? Well, Liam’s Liamness simply doesn’t exist, materially at least. Individuality and identity are illusory. This is also not a new idea, dating from the Neoplatonists, to G.W.F. Hegel, to Julian Baggini, though it is often derided by Christians today. In our American context, the individualism of enlightenment giants, such as John Locke, flows through our blood. We are often disturbed by the idea that we are just a small blip on the cosmic radar. We want to say we are independent. We want to be special. But this all stems from the idea that we are even individuals to begin with. Make no mistake: individualism and identity do exist: they just don’t exist in the way we think they do.

Is an arm an arm if it’s not attached to the body? Or is it merely an arm that has been separated from its body? Notice that for the detached arm we have to qualify its status. We use the word “arm” to describe a part of the body that functions best when it remains attached. Similarly, our bodies are bundles of ligaments, and those ligaments are bundles of atoms. Likewise, a city is a bundle of buildings and an army is a bundle of people. Every single classification that I have mentioned has a subset. Notice how a city never stops being a city. We merely recognize that it too has parts. This means that individuals exist, but only in a conceptual sense. We should not fret at this idea, though. Remember, not only is everything in the universe a bundle, but we are the only animal that is capable of realizing this. That thought alone reassures us that man is indeed special.

Let’s look at Liam again. Liam is actually a bundle of atoms that we will call “Liatoms.” Each of theses Liatoms carry specific functions in Liam’s body. It is only because these Liatoms exist that we call their construction “Liam.” Liam exists, but we have to remember that Liam is just a humble construction of these Liatoms. These Liatoms affect every part of Liam’s body. This includes the brain. Every time Liam thinks, it’s really the Liatoms arranging in certain ways that command Liatoms in other parts of the body to act together in certain ways. Liatoms react to environmental factors, as well. The part of Liam’s brain that issues commands is called the subconscious. At the same time, certain Liatoms behave in a certain way that makes Liam aware of his actions. The part of Liam’s brain that realizes decisions is called the conscious. In the past, neuroscientists believed that the conscious played the dominant role in decision-making. However, many modern Neuroscientists have concluded that the subconscious makes decisions before the conscious is fully aware of them. If Liam raised his hand, the command to raise his hand would have already been in process before he actually realized he was raising his hand. I hope you see where this is going.

Looks like Disney was onto something…

Finally, Free Will

Alright, alright. I’m sure many of you are disappointed that I haven’t even gotten to the “free will” part of my argument. Unfortunately, though, the history and background of this subject is so extensive that it demands at least a few paragraphs concerning them. Let’s get to the point then.

If Liam’s brain decides he will raise his hand before knowing he’s going to raise his hand, did Liam actually have a say in determining his action? This, again, opens up a flurry of glorious implications that many Christians (yet again) find uncomfortable. And I can see why. We’ve been conditioned to believe in our individuality, as well as the “fact” that our free wills make conscious decisions. This is not the case. Notice, however, that I have not said that free will and individuality “don’t exist.” I said that they were “illusory.” This is because I believe that the way post-Enlightenment culture has observed and taught free will is largely flawed. From an early age, we are lead to believe that free will is more than just a concept: it is a function that individuals take in actively making decisions throughout their daily lives.

When Liam steals from Eduardo’s (a former Clarifying Director) cookie jar, Ed will most likely ask Liam why he chose to do that. Harris would argue that Liam didn’t choose to steal anything; his Liatoms (which make up his body) commanded him to. Remember this. We will return to this totally not made up scenario.

Before we address the above situation, we must discuss yet another fantastic debate that scholars have engaged in throughout history. What matters more in the person’s development: their natural disposition or the environment they’re exposed to? Was Ed born liking comic books or did his family raise him to embrace them? A lot of Harris’s view of human nature can be seen in the work of Sigmund Freud, who stressed the environment’s impact on the psyche over the individual’s will. While I tend to agree with bundle and subconscious theories, I am not entirely sold on the idea that we are totally reliant on our environment. This is because our minds are self-regulating. Yes, we need oxygen, water, food, etc. However, unlike the dog and his dog atoms, Liam and his Liatoms can expand their mind’s capacity merely by self-reflecting. It’s not that animals cannot accomplish this, rather humans can do it on a level of greater complexity and dexterity when compared to our beastly neighbors. Thus, the somewhat autonomous nature of the mind is important to factor before simply stating that we are entirely at the mercy of our environment. This gets really meta really fast when you think about the fact that the brain is a part of the person’s environment, itself, that impacts its own environment but still has a dependency on another environment which is perceived by… Ironically this stuff can give you a headache really quickly.

Another idea I cannot bring myself to approve of is determinism, the concept that our decisions are entirely subject to fate and the environment. Let’s say that Liam is confronted with five paths on his walk to the Vatican (where else would he be going?) He picks path two. Free will defenders would exclaim that Liam could have chosen any one of the paths. Harris’s friends may contest that, stating that it is because of Liam’s biochemistry that he performed the action. There was no conscious choice made by Liam. According to determinism, Liam’s chemicals already made up their mind before he was even aware of any options. Regarding other paths, Liam never had a chance.

This is where determinism starts to struggle, though, in my opinion. Let’s bring back the concept of self-reflection. Let’s say that Liam finds himself in the middle of a maze. He can go left or right. If he goes left, he can leave the maze. If he goes right, he will warp back to the start of the maze. Liam chooses to go right. According to determinism, Liam, who is totally at the mercy of his environment, would have to keep choosing right eternally. This doesn’t seem so realistic, and implies a great authority that the mind has due to its self-regulatory processes. Liam, I can assure you, would certainly choose a different direction upon realizing that going one direction simply doesn’t work.

Guess he should’ve turned left.

Guess he should’ve turned left.

What IS Free Will, then?

My least favorite philosophers have to be the ones who deal in strict absolutes, when there is a middle ground that can be found. Many will claim that “free will doesn’t exist,” and while I think free will is misunderstood, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Some will even go as far to say that choice doesn’t exist, as shown in the Matrix film franchise. To that, I must say that even if our awareness of decisions is not immediately apparent, there is still a decision that is made by chemicals in our minds. These chemicals, again, are continuously modified by boh our experiences and self-reflection. Something wins out. Otherwise, we would be a jumbled mess of indecisive vegetables.

I’ve spent this entire reflection writing about what free will is not. So, what is it then? In my opinion, it has nothing to do with making decisions, and instead describes our ability to will (or carry out) actions that meet our desires freely (that is without exterior interruption). Let’s say Liam wants to steal Ed’s cookie. Liam’s mind has concluded that it will engage in the act of stealing. Liam wants the cookies and seeks to will the action of obtaining them. So long as Liam has a clear path to willing his desire, he is free to do so. Liam can exercise free will. Now, let’s say that Ed constructs a giant bushel of broccoli around the cookies, and the only way Liam can get the cookies is by eating his way through this coating. Liam, fearing the foul vegetable, is now unable to will his desire, and thus loses his free will in this situation. This version of free will is much more environmental, as Liam’s subconscious craves sweets, but it also recognizes the value of the subconscious’s self-reflective agency, as Liam’s subconscious fails to see the wrong in stealing.

“Free will is the ability to will our desires into reality without external interruption”

I must admit that I still grapple with the concept of free will, though this seems the most practical and relevant definition I could conjure following my research. As with all definitions, though, it is subject to refinement, as all definitions should be.

*Flips the switch to mess with our neurons*

“That’ll show them to eat my fruit again.”

What this Means

Here’s an important note. Harris and company do not throw out morality and accountability. In fact, none of this changes too much about good and evil, which can be summarized as that which is beneficial and detrimental to the overall state (spiritual state included) of humanity. Instead, morality becomes less about choice and more about state of being. Let’s envision this below:

Scenario One: Liam steals Ed’s cookie. Ed calls Liam before a Vatican Council, which concludes that Liam had the full capacity to choose otherwise, so he must be swiftly punished. They sentence him to excommunication as a punishment for his actions, as the Third Vatican Council stipulated cookie stealing as a mortal sin.

Scenario Two: Liam steals Ed’s cookie. Ed calls Liam before a Vatican Council, which concludes that Liam’s misdeeds were a consequence of the circumstances of his malformed mind and detrimental environment. Rather than punish Liam, they seek to help him, while still protecting all of Ed-kind by imprisoning Liam until he no longer poses a monstrous threat to society.

Freud often viewed misdeeds of mankind as coming from a disordered mind. This means that there is no such thing as a “perfectly sane” person suddenly committing murder because “perfectly sane” people do not act in such a manner. By their actions, these people demonstrate that they need psychological help. Thus, rather than imprisoning people for the sake of “eye for an eye” punishment, people should instead be imprisoned if they pose a threat to society and their malicious subconscious state has not been reformed. This has major implications over the way society deals with criminal justice.

He didn’t have a choice! He’s addicted and needs our help!

So What?

One of my tendencies as a writer and video producer is to forget that Clarifying Catholicism, the project I created, is a Theology website. This is because I rarely talk in theological terms, and for good reason. My goal isn’t to reform theologians. Instead, I seek to delve into the wing of reason that has enriched our faith for ages. That said, these secularistic musings do carry a great weight over how our Church should interact with people.

For starters, we are not individuals in the sense that we are materially unbound and unstable creatures who cannot sustain ourselves alone. We are all parts of one great body, and we are called to act “together with others” as Pope John Paul II would say. Hegel really enjoyed this idea, which I have begun integrating into my own faith life. He writes that the person with an individualistic mindset deems their challenges, struggles, and sufferings as significant, propping them up on a fake wall of individuality. When we think only of ourselves, it’s easy to lose sight of man’s common good, and our failures and sufferings begin to drag us down. When we think of ourselves as a part of a greater collection, we feel good when we suffer, knowing that our efforts are dedicated to the preservation of the common good. Suddenly, once the wall of individuality is torn down, a drop of blood that can ruin a cup of water becomes harmless in an ocean of man’s goodness. Our common bond strengthens us, as it challenges us to look at humanity in a broader sense. I am no longer “Will the Individual.” I am “Will the Part of Christ.”

“Tend my sheep,” (Jn 21:17). These ideas of individuality’s failures and the subconscious’s supremacy actually mesh quite well with the realization that if another part of Christ’s body is suffering, it is because it is hurting and requires healing. My favorite metaphors of ministry have to do with medicine, quite frankly because I think it is the Church’s fundamental role to repair a broken humanity. All too often, when I find myself hurt by the actions of others, I ask God “How do I help those who hate me?” God then responds “These are my children who are starving from spiritual malnourishment. Whatever suffering they cause you, they feel many times more. Tend to them as such.” Shifting this mentality makes all the difference in the world when you ask yourself if you are punishing sinners or helping lost lambs find their way back to God. If Freud was right, that people act inappropriately because they have a neurological disorder, then I would argue just the same for sin and vice. Anyone in their right mind would “choose” not to sin. But we aren’t in our right minds always. We require constant self-reflection and attention, but the man who is spiritually disordered will never be able to nurse himself back to spiritual goodness. Once the mind convinces itself that a certain action is appropriate, it is incredibly difficult for it to break its cycle of sin. In summary: we bundles of flawed subconsciouses need each other to truly realize the body of Christ.

The people on the outside are just misunderstood

The people on the outside are just misunderstood

Clarifications: Answering Some Questions I’ve Been Asked

- What if you’re wrong? Here’s study X that shows we actually are conscious of our actions as they occur?

- Sounds great! Please keep in mind the disclaimer that says “Theoretical Applied Theology.” The moment someone can persuade me to reverse this theory of mine, I will. I am a fallible person, and neuroscience has a long way to go before any conclusions are made. In fact, by its very nature, Empiricism can never ascertain certainty. That said, this notion of subconscious versus conscious thinking is a very real possibility, and so long as it remains a very real possibility, it demands investigation. So, consider this article a “what if” scenario if you find the opposing school of thought more appealing. Personally, it makes sense to me that we engage actions before we fully realize them. It almost makes sin make more sense. After all, if we were fully aware of our actions, I feel like there would be a lot less sin in the world. The fact is, that a lot of sin is rooted in deep psychological and emotional distress. My model of free will still lets the subconscious, which is still animated by the soul (in theological terms), make decisions. The biggest change here is that by altering the language around free will, a greater burden (or calling) falls on us to actively help others who may be damaged.

- Sam Harris was an atheist fiend. He is not a credible source of information and he cannot be trusted.

- Right… Because a set of beliefs can totally make a person into an irredeemable mess of lies (sarcasm). This “argument” always disappoints me. Every single one of us is quite flawed, both Catholic and non-Catholic. Think of it like this, too. Religion is a language that cultures use to express how they see the world. But there are also languages of science, philosophy, psychology, anthropology, etc. All languages have some level of truth in them, and to truly foster dialogue, we need to translate and clarify a few terms. Anymore, it is very difficult for people to engage in cross-discussion between fields, and I think that is a shame. It seems like if someone can’t speak the language of Catholicism, they are often written off as totally illogical. It happens both ways. We are all God’s children blessed with faith and reason. Sometimes, people only focus on the latter. Let us reach out to these people and engage with them where they are at, while acknowledging the valid perspectives people can bring into discussions.

- What about the soul? This science stuff is cool and all but can you talk more about that?

- Sure! Obviously, I believe in a soul. However, you will not catch me dead (as my soul leaves its material body) using it in a moral argument ever. Here is why. A brilliant philosophy professor of mine once stated that at a certain point in metaphysics, you end up with the phrase “Because it is a mystery.” “What came before the Big Bang? It’s a mystery.” Beyond that we can’t go much further in intellectual discussions. Funny thing is that the “Because it’s a mystery” phrase gets pushed back more and more as science progresses. A couple hundred years ago if people asked what the material cause of certain diseases were, they would say “it’s a mystery.” Go back a few thousand years and the soul itself was tied to sickness. Here’s the thing. The soul is the fundamental animator of all life. Saying that the soul caused something is akin to blaming oxygen for everything. How does the man run? Because of oxygen. Why did you say that? Because of oxygen. To add an additional layer of complexity, unlike oxygen, we cannot speak of the soul in materialistic terms. So yes, I can say “I have free will because of the soul,” but what does that mean? I may as well say “I have free will because it’s a mystery” since once you hit soul you can’t ask too many more questions. For now, I’m comfortable saying that our subconscious is our soul in action, and that the tiny little atoms and particles that compose us are manifest through the soul. Essentially, science can be seen as a lens through which we understand the effects of the soul, rather than the soul itself.

- There’s not enough theological language in here. Isn’t this website about Clarifying Catholicism?

- Well, again. As Catholics, when we engage in discourse about scientific topics, we have to use scientific language. Of course, these subjects should blur in together when looking at humanity from a holistic perspective, but when we dissect them, we need to talk about the material in material terms, and the spiritual in spiritual terms. I don’t want to get into dualism (yet), but it’s pretty clear according to the Gospels that there is this chasm between God and man that is infinitely large to cross. Only God can cross it, which means our study of the spiritual are contingent on what He chooses to reveal to us. We have no way of studying how the soul pragmatically works. So, for now, let’s focus on what we can determine from the senses, which is the material.

- This seems like an impractical debate.

- I get it. However, as I mentioned with the Liam and Ed situation, the ramifications of this are massive. How we deal with criminals largely has to do with the idea of choice. If criminals have a full independent capacity to choose their actions with good conscious, then by all means they should be punished swiftly and harshly. If not, though, it means that criminals who commit crimes do so because of some deep-seeded issue in their subconscious that requires attention. Consider two bank robbers: one who requires quick cash and another who was raised to steal on the streets their whole lives. How would juries look at them under the competing views of what free will is? Would they receive the same sentence? Or what about a man who killed someone fifty years ago, never got caught until now, but has turned their life around since it occurred? Should they be punished because of a choice, or should they be let go because they have demonstrated improvement in their neurological welfare? Apply the situation to a 90-year-old Nazi found in South America. Huge ramifications…

- What about getting drunk? By your definition do we still have free will?

- Yes, you do. Please remember that my definition is a sociological one, not a neurological one. In a sense, I suppose this does mean we don’t have a neurological free will. But the term “free will” was never really a neurological one to begin with. Even the idea that “free will is a term to sum up the decision making process as a whole” is nothing new. A drunk person is just a person whose subconscious and conscious is impaired, as he cannot think about or realize actions as he would if he was sober. Then again, doesn’t hunger affect our decisions, too? What about pain? Where exactly is the line? For me, there is none, as I take the neurological concept of free will out of the picture, and assign it a greater social value. Also, Remember that I’m a politics major, so I could be a little biased. But for me the importance of free will isn’t in making an decision, but actualizing it. Does the United States Constitution protect our ability to make choices? No. Actualizing them? Yes.

- Isn’t this predestination if we have no control over our actions?

- I can definitely understand why this question comes up. However, I must again draw attention to the mind’s self-regulatory nature. This makes us quite different from animals, who aren’t subject to predestination but sure act like they are through their very predictable patterns.

- This theory is inherently against Church teaching. Let’s excommunicate him! After all, Aquinas says…

- This is addressed to those who will only hear philosophical arguments if they came before the scholastic period. While they constitute a minority of the broader population, they are quite vocal. I adore Aquinas. I really do. However, a lot has happened in the 700+ years since he died, and some Catholics enjoy pretending that academia died with him. Worse, still, many can’t get over the Enlightenment’s stronghold over modern scholarship after it replaced scholasticism. As Catholics, we are called to interact in an ever-changing world. Aquinas is relevant, but so are Locke, Kant, and even Nietzsche. For a long time now, secular and theological studies have been kept separate (an Enlightenment style), and I would argue this is actually a better approach to what we had before. On the other hand, the Enlightenment perpetuated some pretty questionable ideas (the modern view of the individual which I ragged on earlier in the article is an Enlightenment idea), and even more horrific results (such as the French Revolution). Every time period has its merits and shortcomings. I personally like bridging the gap between scholasticism, the Enlightenment, and the post-Enlightenment, but these ages are not exclusive in wisdom. Aquinas was brilliant. He was one of the most intelligent men to ever walk the Earth. However, he was not Christ, and as comforting it is to cling to him as a security blanket of sorts, it’s time to acknowledge the intellectual merits that other traditions have to offer. Furthermore, I must state that without integrating theology into a pragmatic perspective, it will lose all of its lifegiving energy. Just as new scientific theories are put forth every day, we must do the same with our theological ones as well. We are not a church of dead dogma, so in the end of the day, I might reverse course on my opinion or disavow this entire article. People may shoot down this article, but at least I will be able to say I offered an idea eliminated one option regarding the free will debate. We need more Theologians testing the boundaries of our faith for the sake of growing closer to truth. Otherwise, there may as well be no Theology majors at all, and Theology as we know it will become dead dogma.

Summary: TLDR

THE PROBLEM

- We are bundles of material

- e.g. eyes, ears, atoms, particles, remember that the soul is immaterial.

- It is only due to convenience that we call ourselves “individuals” as we are made of bundles, but we also construct bigger bundles.

- e.g. we are a bundle of atoms, a crowd is a bundle of people

- Thus, individuality exists as a concept, we define it as a bundle of smaller units that compose what we call a person.

- e.g. there is no such thing as the material Will Deatherage. I am just a collection of things that I call Will

- Our brains are bundles of atoms and chemicals bouncing around

- Our consciousness is also made of biochemical bundles

- According to neuroscientists, our brain makes decisions before we are conscious of them

- Decisions are not made by our conscious, but rather our subconscious, which is the part of our brains that heavily influences decisions.

- The environment our atoms and chemicals are exposed to significantly impacts our behavior

- Unlike other animals, though, our minds have a higher capacity to regulate and refine themselves without exterior influence via self-reflection, which is the act of contemplation without significant exterior influence.

- g. just by sitting there and thinking about free will, you are already reforming your subconscious

- Therefore, our minds are not deterministic, as a person trapped in a maze that never ends in one direction would quickly realize that they should try another direction through the self-regulation of the brain

- This is a famous thought experiment where a person is trapped in a maze. If he turns left, he will be free of the maze. If he turns right, he will warp to the beginning of the maze. If we are deterministic, the person choosing right will always choose right. This is not the case, thanks to self-reflection.

- However, a flawed mind will continue to regulate itself in a flawed manner, unless an exterior factor corrects it.

- Free will has been defined in the past as the ability to make conscious choices.

- However, we have shown that the conscious is not in charge of making decisions and is only aware a decision has been made after it occurs.

- Free will, then, has nothing to do with a conscious choice.

- Some conclude that free will doesn’t exist, then.

- I argue that free will exists but needs to be defined better.

THE SOLUTION

- People have desires

- By saying we have desires, we acknowledge something that we seek to “will.”

- We seek to will our desires without obstruction, “freely.”

- Thus, free will should instead be defined as “the ability to will our desires into reality without external interruption.”

- According to this definition of individual, subconscious, and free will, people who do wrong do so not because they choose to, rather there is something disordered with their decision.

- There is, then, a difference between good and bad parts of the subconscious, which can be changed through external impacts and self-reflection.

- Law and order should not focus on punishment for the sake of wrongdoing.

- g. a person who robs a store should not be punished excessively for the sake of punishing, especially if they show indications of reform during their sentence.

- Law and order should instead focus on preserving the common good of society until the wrongdoer has learned to correct their behavior.

- By doing this, we can better reform the criminal, rather than just punish them for the sake of punishment.

CONCLUSIONS

- By recognizing that the “individual” is really an abstract concept, and that we “individuals” belong to a larger bundle of humanity, we are able to collect meaning from our suffering, especially when it benefits the common good of humanity.

- Individuals cannot sustain themselves on their own.

- A society where the term “individual” is recognized as an abstract concept can focus on acting together with others, rather than alone.

- When we recognize the role we play in the larger human race, we are able to better unite ourselves with the body of Christ.

- When we recognize that people are not entirely in control of their choices, and that many people are victims of circumstances, we can better work towards healing them.

- Because a damaged subconscious will often fail to regulate itself, we are called as Christians to actively reach out to people who suffer from psychological damage that leads them to make damaging decisions with love and mercy.

- However, it is just as important to realize that there are good and bad parts of peoples’ subconsciousness and that people who show excessive signs of instability should be detained from society, which deserves protection.

- We must aim to build a world of justice and mercy that reflects God’s will. Only then will we realize Christ’s vision of creating a society where true care is administered to those who do wrong, who are actually misguided sheep in God’s flock

References

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/phenomena/2008/04/13/unconscious-brain-activity-shapes-our-decisions/

- https://www.verywellmind.com/conscience-vs-conscious-whats-the-difference-2794961

- https://samharris.org/books/free-will/

2 Responses