By William Deatherage, Executive Director

The following article is based on what we call Theoretical Applied Theology and should not be taken as dogmatic or doctrinal Church teaching. Its intention is to provoke thought by bringing in outside subject interests to interact with Theology and propose ideas that stretch the imagination, even if someday proven wrong. I appreciate all feedback but would rather wait a little to discern better responses, rather than immediately answering.

ABSTRACT: The existence of observable essences has proven elusive for millennia, as there do not seem to be any material constants in an object’s composition that could explain how it can retain its unity. However, just because we cannot sense essences does not mean that they do not exist. In fact, by observing consistencies in motion, we can see that there exists something that provides objects with their unities. This is important to ethics because knowing what makes a thing a thing can help us understand what constitutes a human person.

Terms Discussed

- Essence: the intrinsic part of a thing that makes it what it is (e.g. what makes a flower a flower)

- Monism: the idea that the universe is made of one single element; this was held by many pre-Socratics, but has recently been revisited by some modern physicists

- Nominalism: school of thought that no two objects are the same and that shared properties are mere byproducts of the mind

- Phenomenology: school of thought that the real world (noumena) exists, but our flawed senses prevent us from seeing reality as it truly is, so the mind constructs its own version of the world (phenomena); this offers a medium between realism (reality is in the object) and idealism (reality is constructed by the subject)

- Essential: properties of an object belonging to the essence

- Natural Essence: determined by the characteristics of an object without human interaction (e.g. a tree will grow regardless of human presence)

- Artificial Essence: determined by how humans use an object, though an object’s use will be at least partially reliant on its material characteristics (e.g. a chopstick can only be used as a chopstick if there is a human to use it)

- Conceptual Essence: determined by how humans respond to interactions with objects; these are independent from any material object, and instead rely on the quality of experiences that humans can have with several different objects (e.g. the concept of pain is non-existent without humans and is not tied to the characteristics of any one object)

SUMMARY (TLDR) OF THIS ARTICLE IS BELOW IF YOU SCROLL DOWN

Background

What makes a thing a thing? What is tree? What is chop stick? What is Gideon (one of our writers and recent convert from Orthodoxy)? For millennia, philosophers and theologians have grappled with this question. And while this subject may seem trivial, its implications can have life or death consequences.

Essence. This term was popularized by Aristotle and treasured by the Scholastics for hundreds of years. An essence is what makes a thing a thing. That chopstick, tree, and Gideon all have something about them that is essential to their nature. Without it, Gideon ceases to be Gideon, tree cannot be tree, etc. But does this viewpoint hold up? Modern scientific methods have demonstrated that we live in a constantly changing universe on a subatomic level. Even poor Gideon is a material mess of atoms swirling about as he stumbles to theology class. Or, is an essence immaterial? Is it spiritual? If so, how can we know if two things have the same essences?

To illustrate this more clearly, let’s look at a desk. Now, a desk has many components to it: a flat surface, a few legs holding it up, possibly some screws keeping it together, etc. What if we take off a leg, though? Maybe lose a few screws. Perhaps we cut the flat surface in half. Is it still a desk? If not, when did it stop being one? What is essentially required for the desk to still be a desk? This may seem quite arbitrary, but let’s think about this from an ethical standpoint. Humans have arms, legs, brains, hearts, and many other components. Let’s say Gideon loses an arm in an arm-wrestling match with his Orthodox friends. Still Gideon? What if he loses his legs while running away from the Facebook mobs that are chasing him down? What if his brain shuts off from reading too much theology (a common side effect) and he is kept alive by a machine? Still human? Working backwards, could Gideon even be considered human, since the average age when of neurological maturity is twenty-five, and he is only twenty? Was Gideon really human back in middle school before his growth spurts? How about when he was a baby? How about before he was born? This is precisely why understanding essences is important, not simply to theology, but ethics, politics, social science, medicine, and so much more.

So, if an essence is material, where is it? If it is metaphysical or even spiritual, how can we even talk about it, let alone know it exists? I am no expert when it comes to metaphysics, which is the science of things that are immeasurable by standard physics. That said, my curiosity regarding this issue grows every day, and I am eager to spark more discussion on this subject.

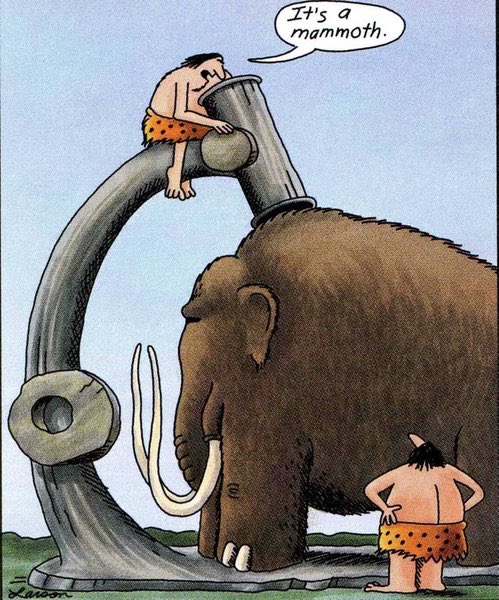

Or is it just an elephant with hair?

Or is it just an elephant with hair?

Start with the Stuff

Let’s start with objects themselves. I’ve talked about bundle theory in my article about free will a while back, but I suppose a refresher might be in order. Basically, bundle theory is the idea that all material is just composed of bundles of smaller materials; there is nothing that materially stays the same. The view denies a material essence, and at face value seems reasonable. As I stated earlier, there really isn’t much in our chemical or atomic structure that remains constant. Our atoms are constantly in motion, impacted by thousands of chemical reactions every second that we never notice.

That said, there is still some consistency at play. After all, if the universe was a disorganized mess of atoms, there would be no coherence between any object and it’s likely that even human speech would be unintelligible, assuming we could even exist in a total chaos to begin with. So, there’s this problem. The universe is obviously organized on some level, yet we fail to find any material constant that can explain how this is. There is a theoretical solution to this, though.

David Bohm was a renowned theoretical physicist who also had a keen interest in the nature of consciousness. In his later career, he delved into monism, the idea that everything in the universe constitutes a greater wholeness. In simplified terms, when we break the universe down to its most basic building-blocks, we end up with the same material substance. This theory was pioneered by the pre-Socratics, who claimed that the universe was made of a single element, such as water or fire. This was later scoffed at by the Enlightenment empiricists, but it has recently made a return to the philosophical and scientific scene, thanks to scholars like G.W.F. Hegel and Bohm. When you think about it, the idea that we are all made of the same subatomic material may not be so farfetched, considering the fact that the same particles found in stardust are present in humans. Because of this, Bohm figured that studying physics in terms of particle construction was rather futile, as we would only break things down further and further until we wind up with one material. Instead, Bohm preferred to analyze the effects of non-material forces on particles. His interest in energy may have contributed to trends we see today in some branches of physics, which are more concerned about the energy that affects material substance, rather than continuously breaking said particles down.

On one hand, this theory bears striking resemblances to a few core Christian ideas. We are physically united to the universe that God created for us, just as we are welded to the Body of Christ on a spiritual level. For further reading regarding the implications of this idea, I recommend Hegel. This leads to another problem, though. If everything is made of the same thing, but pieced together on a subatomic level in very different combinations (due to the energy that impacts us), how can we understand what makes a tree a tree or a man a man?

Between Bohm and Bowie, “Starman” sure takes on a new meaning. Speaking of which…

Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

Nominalism is the idea that no two objects are the same. Its supporters commonly reject universal properties that are shared between objects. If two objects look red, for example, they really aren’t the same shade of red; they’re just close enough. This viewpoint seems to mesh well with our atomic situation; again, while we might be made of the same stuff, the energies that flow through the universe have molded us into very different things. When two objects, like two trees, two chopsticks, or two Gideons, look similar, well that’s just it. They look similar but they’re not the same.

This seems to address a few of the issues with material essence, but it seems rather reliant on the way we perceive things. Sure, two trees might look the same, but there still seems to be something about the tree itself, separate from my observation of it, that allows for me to perceive it the way I do. My personal love for Kantian phenomenology comes out here. The rationalists said that ideas came from the mind alone. The empiricists said that ideas come from the objects we interact with alone. Phenomenologists say it takes a bit of both. According to Kant, the reality we experience and the reality that is actually there are two different realms that interact with each other. The former requires the latter to observe; the latter requires the former to be observed. This allows for a bit of compromise in this issue.

How about this? Is it possible that no two objects are materially the same in a manner recognizable to humans, yet there is some unobservable force within them that causes them to act in a way that we can track by repeated observation? Hold a microscope up to two pieces of flint. Night and day differences on a molecular level. However, take a piece of steel and strike it against the flint. Every good Boy Scout can expect a spark emitted by this chemical reaction, and every good chemist will know that this will always happen no matter what. Yet, on a subatomic level, no two pieces of flint are exactly the same. How can this be? It seems we can observe some repeatable chemical reaction, but there’s no material consistency within the subatomic makeup of flint and steel. In Kantian terms, the essence is there; we just can’t fully grasp it. We can see that it exists, and we can see its effects, but we can’t track where it is or why it’s there. Perhaps the essence is metaphysical, or even spiritual.

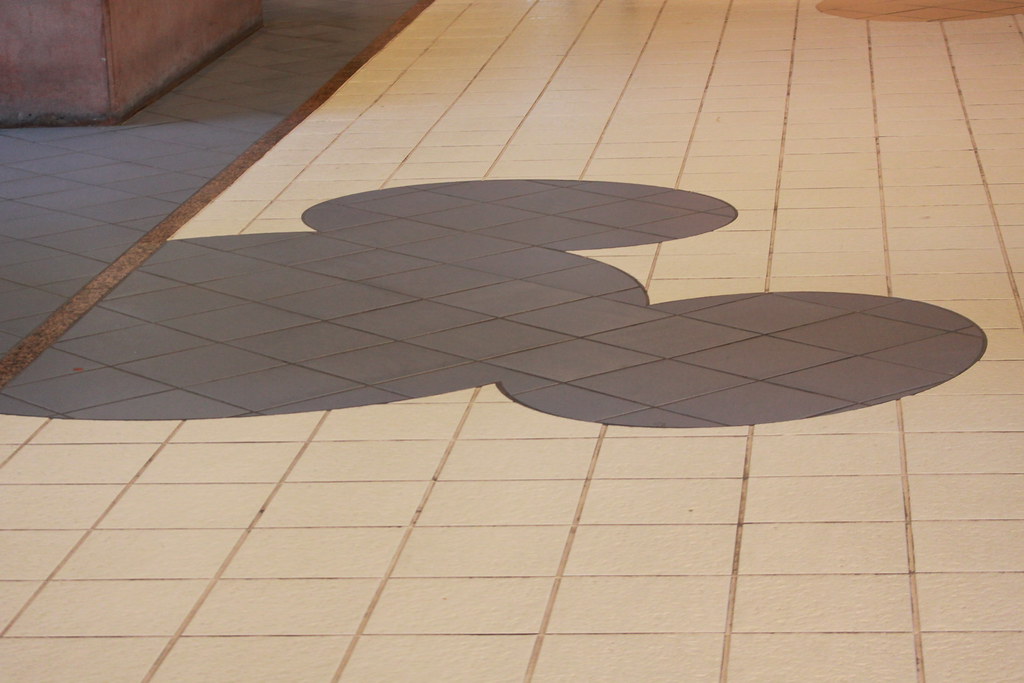

I know something’s casting that shadow, but I don’t know what it could be…

I know something’s casting that shadow, but I don’t know what it could be…

Categories

Phenomenology relies on both the subjective observer and the objective reality to generate knowledge. When we experience something for the first time, we tend to categorize it. For example, did you know that water puts out fires? We see this every time the firemen roll up around the Fourth of July to some poor sap’s barbeque. Over thousands of years, we’ve witnessed water put out fire with no significant exceptions. When Aristotle talks about essences, he usually mentioned their material effects. In this case, Aristotle would say that it is in water’s nature (which comes from its essence) to put out fire. Did you also know that water, the same substance we use to put our fires, helps us to live? Now we can say that the essence of water is to put out fires and sustain human life. This manner of involved categorization of essence was brought to greater attention by existentialist Martin Heidegger. In the past, many Scholastics, Rationalists, and Empiricists preferred to study the nature of objects in an isolated manner. To best study water, we abstract the qualities of water by isolating water from other substances when we observe it. We study “water as water.” However, Heidegger changed the course of this practice, instead suggesting that the best way to learn about the properties of an object is to observe how it relates to others without preconceived judgments at play. Thanks to Heidegger, we now remember that it is best to study water when we see how it reacts to other substances. Perhaps Aristotle said it first, but Heidegger brought it to the forefront of metaphysics in an age when the involved observer had become lost.

So, to see essence in action, we test things over and over, and over again. But how can we be certain about whether or not thing one has the same essence as thing two?

I’ve mentioned that just because we cannot observe essence, it does not mean that essence doesn’t exist. Thomas Kuhn’s Nature of Scientific Revolutions makes a similar Kantian claim that objective reality exists; we just can’t see it. Much like how we cannot see God but still observe His effects, the same applies to essences. We experience that water is different from milk because the way water interacts with flowers is observably different than how milk does (trust me; enough middle school science fair projects have demonstrated it). Once we observe said effects, we recognize a greater reality at hand and categorize.

Imagine you’re stuck on an island of only dogs. For years, the only wildlife you interact with are dogs, so you categorize dog as “animal.” While most people would understand that the category “dog” is different from that of “animal,” you wouldn’t. Despite the differences in categorization, the dog’s essence stays the same, though. This distinction between essence and categorization is key because it reminds us of our insignificance to the majesty of God’s creation. One second we might think we know everything there is to know about water. But that is impossible. Only God can know the fullness of anything; He knows our own essences better than we do. This may seem stressful, but I personally find it rather exciting; it means that no matter how well we think we understand something, there is always more research to be done. Wonder is limitless.

I feel like we MIGHT need more categories than that

Natural, Synthetic, and Conceptual Essences

One last thing before we dive back into theology. Are there different types of essences? Let’s go back to Gideon, the tree, chopsticks, and throw in games for good measure.

Take the tree, first. I mentioned that our approach to categorization should be reliant on the constant changes we can observe. I also mentioned Heidegger’s renewed concept of an interested/involved observer, how interacting with the things we study can yield greater understandings of the effects of their essences. But a tree grows on its own. It does not need any interaction with us to function. In fact, all trees grow without our mediation, just as all fish swim on their own. These are natural objects, or things which when left alone behave according to their own essences. They objectively function in certain ways that are independent of how we perceive them. This implies that the best way to study natural objects is to minimalize human interaction with them, or at least keep it to a minimum (our flint and steel example required a little push from us). This may seem counterintuitive to Heidegger’s involved observer, but even he recognized the need for some sciences to stay empirical. And yes, the way humans interact with nature can have some bearing on their essence, but the distinguishing characteristic of nature seems to be that without us, these objects behave in an objective manner on their own. When we study nature, we study the world we were born into. And because we did not fashion nature, the natural world gives us the unique opportunity to study it from a more objective perspective; one which allows us to learn more about our origins, environment, and surroundings.

How about chopsticks, though? While our neighbors in Asia enjoy using them to eat, us Americans would rather use our similar skewers to spear meat on a barbeque. Do they not appear similar, though? What is preventing chopsticks and skewers from having the same essence? Welcome to the artificial world. If somehow God materialized a chopstick and a skewer and set them side by side in an Antarctic glacier, I highly doubt either object would behave in a manner distinct from the other. It appears, then, that without humans to interact with them, the essences of artificial substances are rendered insignificant, if not nonexistent. But once humans are introduced to the picture, we begin to use these spears/sticks in very different ways, so our cultures develop different names, different categories, for them. It appears, then, that the essence of the artificially constructed object is dependent on how humans use it. At the same time, though, the physical qualities of the object are still very real. This makes the artificial object’s essence, unlike the natural one, intersubjective.

The last category gets even trickier. What is the essence of a game? Unlike natural and artificial objects, concepts are entirely immaterial, meaning they are incredibly reliant on human cognition and there is no strict material basis for them. What are games? What are numbers? What is justice? Numbers and mathematical properties might be easier, as they are common to all shared experience (I can assure you that there does not exist a single man who has never experienced number before). But what about concepts like justice, sorrow, happiness, etc. Such ideas, being quite reliant on human thought, prove difficult to find a common essence in, as what is just to me may not seem just to you. There is a great temptation to say that concepts are totally subjective, but as we can tell, humans are indeed able to communicate concepts to each other in an intelligent manner. Just like nature is dependent on objects as sheer objects, perhaps concepts are dependent on experience as sheer experience. For example, getting hit in the head hard enough will likely hurt. And when it hurts, we experience something very similar, regardless of what object hurt us. From this experience, we develop the concept of “hurt.” But unlike determining the essence of an object, it does not matter what the qualities of an object that hurt us is. It just hurts. And all humans have experienced something that hurts. Likewise, knowing what a football is, is different than knowing how to play football. The former requires the physical object of football to be interacted with, while the latter requires the act of interaction, itself. So, perhaps concepts are also intersubjective, but they are more dependent on how we respond to interactions, not what we interact with. This is unique to humans, too, as a dog can use an artificial bowl the same way we do, but it cannot understand the concept of just distribution of water as we do. So, maybe between species concepts can be labeled as subjective.

It’s not always like your opinion, man

It’s not always like your opinion, man

Why this All Matters

I still write for a Theology blog, right? I swear each time I post another one of these I move further and further away from theology, but I’d like to return to a question I’ve posed a couple times: what makes Gideon Gideon? More specifically, what makes Gideon a person, and when did he become a person? This whole time, I’ve been driving at the importance of essences as a material unknown, though we can sense their existence via simple observation. To ask “what does a human need to be a human” is quite pointless, in my opinion. “It’s just a clump of cells but it eventually becomes human…” Really? Well when exactly does the material pre-human become actually human? “Six days!” “Six weeks!” “Six months!” Such arrogant propositions attempt to assign weak fallible categorizations to something that is so materially inconsistent. The genetic code of every human is quite different; determining which code constitutes “human” on a whim seems rather foolish: we play God. I must ask: Do we know that water is water because we place it under a microscope and intricately study its water structure? Or do we know that water is water because it acts like all water that came before it? The clump of cells argument is useless; we will never find a definitive “scientific human essence” under a microscope. The better question is “when does a human start to do what only humans can do?” Do baby turtles grow up to be humans? Do apes? Does any other animal? At the moment of conception, a very special process begins; a process that only two humans can initiate and only one human can come out of. This is the most direct effect of a human essence we can see. People ask me all the time why this philosophy stuff matters; this is precisely why.

We know things are the way they are not because we assign fallible categories to material structures, but because we live in a dynamic and often chaotic world where the most miniscule of consistency in motion is noteworthy to scientists. It is also important to remember that even if it may seem mysterious and elusive, there is always a reason for why things are the way they are. We may not be able to know the essences of things, but we can know that they exist by the consistency in their material effects. Thus, no matter how you spin it, there is no better way to see the essence of a natural being, like a flower or a dog, than when we see it grow. Humans are no exception to that rule, and it does not take a religious person or a rocket scientist to understand that.

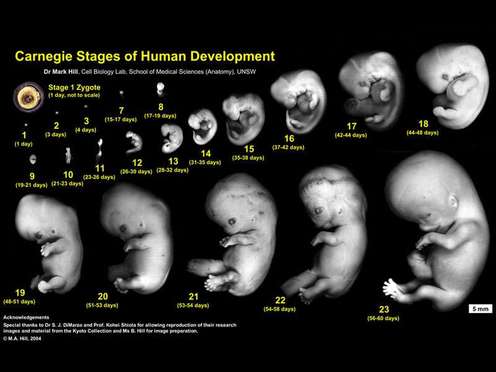

Pop Quiz: When is it a person? (Answer is “All of the Above”)

Summary

- For millennia, philosophers have debated what makes a thing a thing

- Aristotle and his followers settled on the idea that there is something intrinsic that makes something what it is: this is called an essence

- At first glance, this does not seem to hold up in the light of modern science, as there everything around us is constantly changing on a subatomic level; this seems to suggest that there is nothing about an object that ever stays the same, so essences cannot materially exist

- However, just because an essence cannot seem to be material, this does not rule out the possibility of the essence being metaphysical or even spiritual

Starting with Stuff

- On a subatomic level, the universe is a vast mess of inconsistencies; no two grains of sand are even the same, structurally

- That said, there is an observable cohesion between objects

- After all, if we break things down far enough, we end up with a monistic universe where everything is made of the same small building blocks; what matters is not the structure of things, but the energy that manipulates said structures

- This is a surprisingly Christian view, as it seems to support creation out of a single original substance and that we are all part of a greater universal body of Christ

- This raises the opposite problem, though, since if everything is made of the same subatomic material, how can we distinguish anything?

Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

- Nominalism has been offered as a solution to these issues; it suggests that no two objects are materially the same, and any similarities they may seem to share are just the way our minds construct them to appear

- While nominalism seems attractive at first, it seems to put a greater essence on the mind, as if the mind alone constructs reality

- This imbalance can be solved by phenomenology, which claims that the real world exists, but what we sense is a mere appearance of said real world

- The phenomenological world allows for reality to exist in the objects we observe, while still respecting the variations in perception between humans

- Phenomenology also seems to support the notion that essence could be metaphysical or spiritual, as phenomenology holds that it is impossible to sense the real world in its fullest extent, where essences would likely exist

- We can see through repeated experiments that phenomena tend to react a certain way over and over again; for example water will always put out fire; this indicates that there is something about putting out fire that is essential to water’s noumenal essence

- Thus, through repeated observation, we can see that essences exist

Categories

- While we may never understand the essence of an object in its fullest extent, we can observe the material impacts essences have

- Through repeated experience, we can rationally determine what qualities of an object belong to the essence, or are essential

- While many rationalists and empiricists thought they could learn about properties of an object by isolating them and studying them on their own, Martin Heidegger suggested that we best study objects by observing how they interact with other objects

- That said, we can never be too sure about essential qualities, as it is very possible that some characteristics previously understood as unique to one object might later be discovered in another (or vice versa)

- In summary, essence exists; and while we may not be able to observe the essence directly, we can see that it exists by the consistency of an object’s behavior

Natural, Artificial, and Conceptual Essences

- There are many categories of essence, which are dependent on how we interact with different types of objects

- Natural essences perform their essential functions without human mediation; they can be found in plants, animals, and other objects of nature

- Artificial essences are determined by how humans use objects, though the object’s real qualities will impact how it is used; they can be found in any material object that is not natural

- Conceptual essences are determined by the effects objects have on humans; they are totally reliant on how humans respond to interactions and are independent of the qualities of objects; they can be found in ideas constructed by humans, like games and justice

Why This All Matters

- The essence of human, like other essences, is not determined by material composition

- Instead, we can see that human essence exists by the material processes that all humans share

- Humans, as natural beings, grow on their own; their natural growth from the moment of conception shows that human nature begins at the moment of conception

- The “clump of cells” argument that pro-choice advocates support is futile, as we will most likely never find a definitive composition for what makes a human a human; humanity should instead be determined by a common process that we participate in, which is growth from the moment of conception

Edited by Noein

One Response