by William Deatherage, Executive Director

The following article is based on what we call Theoretical Applied Theology and should not be taken as dogmatic or doctrinal Church teaching. Its intention is to provoke thought by bringing in outside subject interests to interact with Theology and propose ideas that stretch the imagination, even if someday proven wrong. I appreciate all feedback but would rather wait a little to discern better responses, rather than immediately answering.

Please be sure to post questions and comments below. I will do my best to address them and update this periodically. Thank you!

“Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth”- Pope St. John Paul II

Abstract: Faith and reason will inevitably arrive at the same truths if engaged with correctly, though reason can only apply to matters of the physical world. God, who is metaphysically perfect, has engineered a world with perfect laws, such as physics and mathematics, that we can understand via the senses. That said, there are some divine truths that can only be realized through Divine Revelation, which we must have faith in. However, while both faith and reason are both integral tools at humanity’s disposal, it is unwise to overlap their terms and language, as faith appeals to the metaphysical, while reason appeals to the physical. Reason should speak on strict material terms, as attributing causation to the spiritual is risky and does not tell us that much about the mechanics of the world. Regardless, both are valuable in our quest to know the material world created by God, and only through faith can we form a relationship with His spiritual entirety.

Terms Discussed

- Materialism (philosophy): The idea that truth can only be understood by interacting with the material world. Not to be confused with consumerist materialism, which is all about valuing possessions.

- Classicists: experts and admirers of scholastic and pre-scholastic philosophy. Most Catholic classicists look to St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, who were influenced by ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle, among others.

- Physical: anything that can be interacted with by the senses

- Physics (traditional): the study of the physical

- Metaphysical: that which goes beyond our capabilities of sensation. It is often accused of being synonymous with the spiritual.

- Metaphysics: the study of the metaphysical

- Noumenal: the realm of existence characterized by an unchanging reality. Everything around us exists noumenally with truths that do not change.

- Phenomenal: the realm of existence characterized by our flawed perception of the real world. Everything we interact exists phenomenologically with conceptions that fluctuate over time.

- Natural Law: unchanging truths in the physical world that can be discerned by reason. It runs parallel to Divine Law but is limited by our senses.

- Divine Law: unchanging truths in the metaphysical and physical world that are determined by God. Thus, only God can reveal them. Unlike Natural Law, these truths extend beyond sensory experience and often address spiritual issues such as how we should build a relationship with God.

SUMMARY (TLDR) OF THIS ARTICLE IS BELOW IF YOU SCROLL DOWN ALL THE WAY

As a politics and theology double major, I have a major pet-peeve: Catholics using theological arguments to justify secular laws. When people ask me what role theology should have in forming public policy, I swiftly say “none.” This controversial statement usually lands me in either a two-hour argument or a two-second classification as a heretic. It only gets worse when I start to defend the merits of materialism, the idea that truth can only be found in the sensible properties of an object. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a strict materialist. There absolutely is a Heaven, soul, and God who love us: I simply just don’t see the value in using spiritual terms to justify secular ethics. As a college student, I often catch the sneers and snickers coming from “die-hard classists” when any Catholic dares to defend materialism. I openly admit that the Enlightenment and French-Revolution, both pioneered by anti-Catholic materialists, left some burning scars across the Church as an institution. Yes, ultra-secularists sought to banish the Church to the shadows of society. And yes, ever since then, the Church’s ideas of transcendent spirituality have been mocked and scoffed by every materialist under the sun. However, I would like to hope that we Catholics can rid ourselves of this bad blood gracefully, turn the other cheek, take a second look at materialism, and try and discern any merits it may have.

Presumably that’s my editor. And by my speechwriter, he means “Will Deatherage”

Presumably that’s my editor. And by my speechwriter, he means “Will Deatherage”

Causation: The Physical and Metaphysical

Everything has a cause, or perhaps it is better to say many causes. What causes the ball to roll? Is it my initiative to push it beforehand? Is it the gravity that drags it along? Is it the laws of physics? Or is it God’s divine principles that command the ball to obey transdimensional rules that are beyond our understanding? Causation is tricky, so many philosophers would divide the subject into two camps: physical and metaphysical. The following definitions will likely come across as reductionistic, but this’ll have to suffice for right now. After all, books have been written on the subject of physical vs. metaphysical.

Physical causation has to do with… well, physical things. Everything we can sense is physical. We are made of material existing in a material world that has material objects to analyze. I pick up the cookie, see it, smell it, and taste it. Yum. What was it that physically caused me to eat this treat, though? Materialists would say it was the bones in my body that worked together in such a fashion that enabled me to act accordingly. Beyond that, there is my brain, which is commanded by chemical reactions occurring in my head that indicate hunger. For every mundane action, there is an observable, tangible, material cause. The subject of physics retains its name because it focuses on drawing conclusions from the sensible.

Metaphysical causation is tricky. In my opinion, it is much more difficult to comprehend than many die-hard classicists would care to admit. You see, before the advent of empirical science, which rely completely on the observable, most scientists, philosophers, and theologians attributed causation to heavenly forces that were divine in every sense imaginable. It wasn’t the brain that commanded my body to act in a certain way, it was the soul. The peculiar thing about a soul, though, is that unlike the brain, it is completely immaterial. We cannot touch or smell the soul as we do with a cookie. “Metaphysics” roughly translates to “beyond physics” for a good reason: it is beyond our sensibilities. To the person who doesn’t understand the difference between physical and metaphysical, it seems like someone can swap out soul for brain, but this is exactly where some serious problems and concerns.

Well one of them has to be metaphysical.

The Problem with Metaphysical Causation

Aristotle and his friends seemed to accept a distinction between physics and metaphysics. To the classic philosophers, there were certain operations that belonged to heavenly bodies like the soul. Animation, growth, perception, thought, and imagination were all operations that the soul directly caused. Today, we no longer use such language to describe these processes. We prefer to say that the plant grows because of chemical processes, rather than a soul animating it to do so. Or, the digestive system causes animals to process nutrients and sustain themselves, rather than the soul. Or, the brain’s complex neurological processes cause us to make certain decisions and behave in certain ways, rather than a soul. Regardless of whether or not you agree, there has indeed been a significant shift to the mentality of the material; this is a good thing, for reasons I will explain shortly.

I have no doubt that Aristotle was absolutely correct when he attributed certain properties to the soul. Yes, I grow because of the soul. I move because of the soul. I learn because of the soul. I also think because of the soul, I speak because of the soul, I write articles because of the soul, I existed and continue to exist because of the soul. Every single action I perform is contingent on the soul operating in my body. I have zero problems with the idea that the soul exists and is the central cause and energy behind all things in the universe… But just think about that for a second.

How special is it really to say that anything is caused by the soul? If we say, “the brain’s thought comes from the soul,” we are actually crediting an action that involves a very complex material processes to a thing we can only understand through metaphysics, scripture, and revelation. Think about it. Everything relates back to the soul. Yeah, we can get into degrees of “plant soul” versus “animal soul” etc., but what good does this do us? A philosophy professor of mine once said, “there comes a point in causation where you hit a wall and have to say ‘because it’s a mystery.’ But there is a special caution people must take before making such a statement, as really anything in life can be attributed to a grand mystery.” For ages, the cause of disease was just “a mystery.” In fact, many cultures attributed sickness to divine origins. Think about the things we used to attribute to the divine one hundred years ago. Think about the things we attribute to it now. Will we still do so in one hundred years? But then again, the soul animates everything around us, so you could justify it as the cause of just about anything. This is perhaps my greatest qualm with using the soul as a justification for any sort of material causation.

I’d say that’s God but… (click here!)

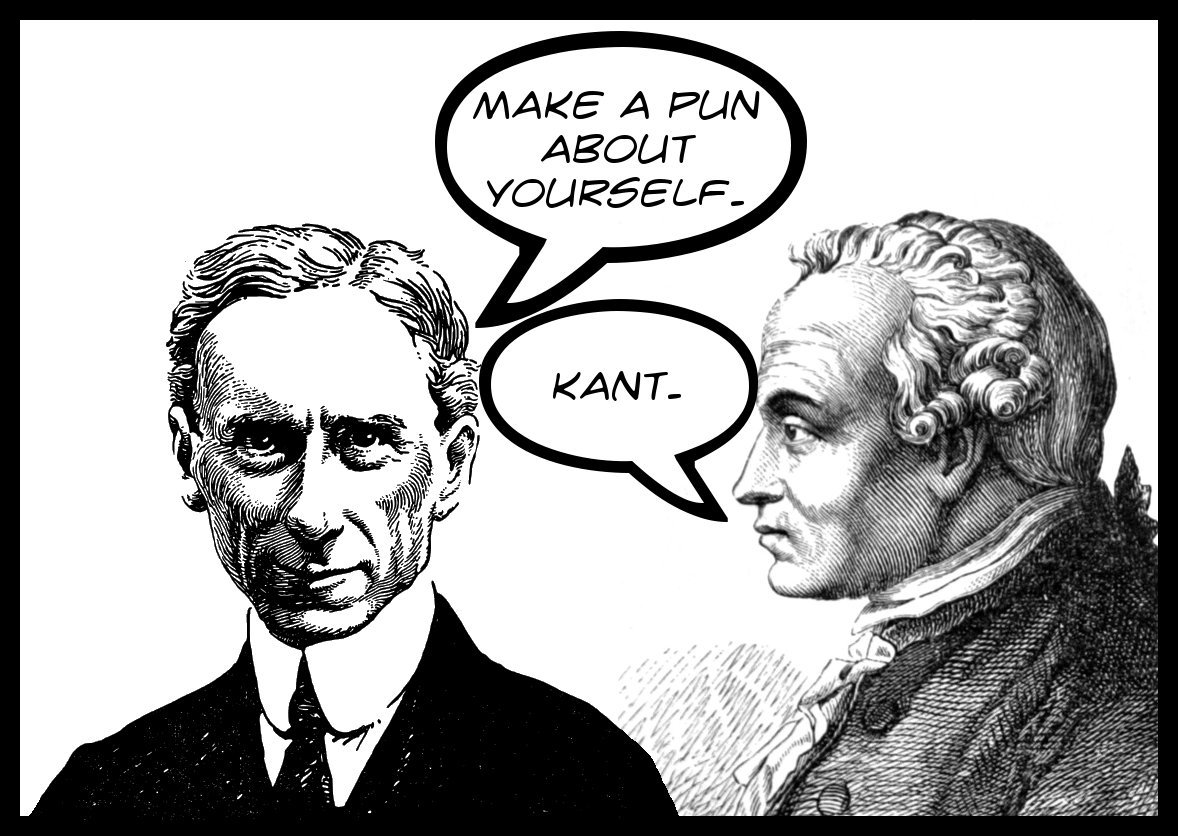

Re-Evaluating Existence: Kant

Immanuel Kant is my (current) favorite philosopher of all time. There, I said it. May as well cancel Clarifying Catholicism at this rate. In all seriousness, though, I can’t say I agree with everything he says. I don’t look into his politics or ethics as much as his epistemology, the study of how we understand things. This is because I firmly believe he illustrates a picture of reality that is truly more complete and humbling than any presented prior. The best part is that Kant did not reject the soul, or Theology for that matter, as many of his Enlightenment predecessors did. In fact, if anything, Kant saved the soul.

I’ve summarized Kant’s basic theory of epistemology a few times, but I’ll give it another go. According to Kant, reality as we interact with it is constructed of two realms: the noumenal and the phenomenal. The noumenal is reality for what it truly is. The totality of all things. The phenomenal is our perception of things. We observe through the senses, and the senses, being flawed, are limited by their material defects. For example, I can’t see so well out of my left eye. If I covered it, I could hardly read the letters of a street sign from a block away. Thus, my senses would detect the word “Cookie Street” in my flawed phenomenal world, when it really says “Dookie Street” (named after a popular Green Day album) in the true noumenal world. Remember that my flawed phenomenological observation does not change the noumenal reality that the sign has certain properties that are completely unrelated to how I perceive it.

Kant’s radical notion allows for an idealized reality to exist while accounting for our flawed senses that construct what we think is true. In a sense, though Kant doesn’t explicitly say this, the noumenal would allow for the existence of a greater metaphysical truth that only God can understand. This indeed allows for divine properties, such as the soul, to work in the world.

But if divine bodies originate from outside the universe, how can we perceive them at all? We can hardly even grasp the essence of the most basic material things. This is where divine revelation comes in. Essentially, our understanding of all things divine is completely reliant on God reaching out to us: His grace. We don’t need grace to study a cookie or chemistry, but we certainly need grace to understand His divinity.

The fact that we are so reliant on God to ascertain truth for certainty severely limits us, but it’s also humbling. A friend of mine who’s a huge fan of Plato once asserted that Platonic form, a divine perfected entity that all earthly objects try to copy, opens up the horizons for observation in a truly noble manner. No matter how well we think we may know something, we can never grasp its true form. If there really is a transcendental greater reality, I take no issue with the existence of form. Unfortunately, though, God is the only being that can truly understand such divine realities.

So far, I’ve basically raised two issues:

- To say something is caused by the soul, or anything divine really, doesn’t say too much, as our entire reality is contingent on a greater metaphysical dimension.

- We are incapable of understanding reality in its totality as God would, and we certainly cannot understand anything metaphysical outside of divine revelation.

Following Kant, Theology and Philosophy largely went their separate ways, the former studying the noumenal and the latter the phenomenal. This introduces a couple of limits to each field. Philosophy, for instance, is reliant on the senses, and can thus never access absolute truths outside of basic ones given by space and time. Theology, on the other hand, can lay claim to absolute truth, but is totally reliant on God, who is the sole deliverer of grace. While the idea that we will never know anything in its totality may at first seem discouraging, I think this actually illustrates a greater beauty. For philosophy, the fact we cannot access the reality, or noumenal, tells us that even the most mundane object is so complex and dense that we will never run out of aspects to study. Meanwhile, Theology remains affixed on God’s revelation, which creates a sense of greater mystery that can be theorized for eternity. Thus, the limitations of both schools of thought turn out to be their saving graces.

I Kant believe I admitted he’s my favorite.

Two Parallel Laws: One Greater

Reality and perception are separate. In Biblical terms, so long as man remains fallen and sin exists, this will always be the case. It is self-evident that our universe acts in accordance with certain laws that remain out of our control. All of these are physical; we literally call them the laws of physics. The laws of physics and other governing bodies that determine universal and human nature are often referred to as “natural law.” We call them that because they are undeniable constants that define how we live. Why does 1+1=2? Because the natural laws of physics command them to be. Why do I have to keep eating cookies to stay full? Natural law dictates that’s how my body works. Natural law is immovable, and it is not defined by us. However, unlike attributing causation to the soul, causation of the material can be traced back infinitely, giving us much more complex material world to investigate. Our guide in navigating Natural Law is reason.

Divine Law is similar to Natural Law in the sense that is remains absolute and out of our control. The difference is that this set of rules isn’t confined to the observable. Divine Law is God’s total rule over not just the physical, but metaphysical too. Think about the Holy Trinity. I dare anyone to come up with a way to prove the Holy Trinity without divine revelation. Divine Law essentially encapsulates all of Natural Law, as God, the architect of this world, commands us to conduct ourselves in certain manners. However, Divine Law goes beyond reason in the sense that it is only by God’s grace that we can even remotely begin to understand it. This is where many modern Christian groups begin to split apart, as some argue that Divine Law supersedes Natural Law, that Natural Law is inherently bad, or even evil. One need only look at the works of political philosophers like Thomas Hobbes to see an eerie illustration of what man is naturally like: a savage who must be tamed by a stable government. This, I think could not be further from the truth.

I always enjoy asking people this question: If God made us in His image, capable of logic and reason, how can the Natural Laws He’s blessed us with possibly contradict the Divine Laws He’s handed us throughout history? Think about it. We live in a pretty remarkable universe. The Natural Laws of physics are constant, our evolution has bred us to be the ultimate combination of dependent rational animals, and Christ’s commandments of love and sacrifice seem to mesh well with our psychological longing for community and eternal search of overcoming challenges. Honestly, what kind of god would create a world where what He commanded us and how He made us were two totally different things: it would have to be a pretty sadistic god in my opinion.

It only makes sense that if we live according to the laws God gave us that it maximizes our human potential. After all, we are called to build the Kingdom of Heaven here on Earth. I would be shocked if Natural Law, which is fueled by our prerogative to survive well and sustain our species, does not match up to God’s grand strategy. Our universe is the greatest machine that has ever been put together. It is an infinitely complex one which can only be understood by studying its intricate parts. However, we are a machine whose architect has properties beyond our own parts. Yes, His essence exists in the parts, and He does sometimes intervene to give us a fix. Unfortunately for us, we will never be able to understand the architect, except for the parts of Him that interact with our parts. Still, the fact that the machine keeps going illustrates the care our architect must have for us. However, just because we can’t understand the architect doesn’t mean we can’t understand how our machine works. We have a manual: Natural Law.

God has blessed us with the gift of perception so we may seek and find better ways of living that satisfy our natural cravings, and they all seem to fall in line with Christ’s divine commandments. Skeptics may have questioned the compatibility of Natural and Divine Law, but I would argue that modern psychology, social science, philosophy, and other such studies continue to remarkably highlight the very teachings Christ gave us. The question many ask, though, is what do we study: Divine Law or Natural Law?

I hate it when people play the God card.

Working from the Ground Up

I’ve talked much about reason, but not as much about faith. Just as reason helps us to study Natural Law (to discern the best path forward for humanity), faith enables us to accept God’s grace, which is again immeasurably out of our comprehension. Basically, when God tells us that something is a certain way, there’s no way around it: it is true. Some people stop there. God said it. It’s true. There’s a couple of issues with this.

- Claims of divine revelation are not unique to Christianity. There must be some measure to evaluate claims people make before accepting them as true. And often times, these people don’t lie: they authentically believe that God has spoken to them. This is where reason can override faith. For example, if someone claimed that God told them that the moon is made of cheese, we could use reason to override their claim of faith. The Church does this all the time before making changes to doctrine. This cements the parallels that run between Natural Law and Divine Law.

- It’s lazy. Very lazy. I’ve already explained why saying “God said it,” “the soul causes it,” or “it’s a mystery” really don’t mean much. God’s essence acts through the material. It sustains the laws that govern the universe and compose our reason. Going back to my machine analogy, it’s almost like someone asking how it works, and is met with “because the maker constructed it to work like that,” or “the electricity powers through it,” or “it’s a mystery. Only the creator knows.” Yes, all three statements are correct. But are they really saying much? And, assuming the machine in this analogy can upgrade itself, will these answers lead us to discovering better ways to optimizing the machine? If the machine of life produces cookies and we fail to understand how our most basic and intricate parts work, how will we ever be able to upgrade ourselves to the next level: the salted-chocolate chip cookie machine?

Aristotle once said that the true artist knows the inner workings of their craft. They understand not just that it works but how it works. This is why I have no issue with neuroscience or biochemistry dictating why we act in certain ways. I accept the idea that my brain is reliant on hormones and chemicals bouncing around in my head. That’s just the material way that the soul works its transcendental “magic” through. For every material cause a scientist throws at me, there is one unchanging soul that remains at my core.

Yes, looking at the material can come across as dry, cold, or even harsh. However, by understanding the mechanics of how our material bodies work, we can only help more people. Two hundred years ago, depression didn’t medically exist. Now we know more precisely what happens in the body when someone undergoes depression. But with great knowledge comes great responsibility, as I would argue that modern methods of dealing with depression are severely flawed in many cases. Regardless, it is because of materialism that we no longer associate disease with spiritual curses. It is because of materialism that mental illness is finally drawing attention it deserves. We understand how and why things happen on a level of greater detail and precision than ever before in human history. Yet, with every new discovery comes a treasure trove of new mysteries to unravel. This is the beauty of understanding the material. If we merely accept faith, which can be easily distorted, we will have no reason to keep asking questions.

I am a firm believer that the revelations God has given us are few and far-between, and for good reason. Christ, the greatest philosopher who ever lived, came into the world to lay down some essential truths, but beyond those, He kinda left a lot up to us. Show me Christ’s signed copy of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. It doesn’t exist because that fantastic work is a product of faith AND reason. This goes to say that we should be EXTREMELY careful in the faith-based truths our Church accepts. While we may laugh at the notion that the Church shouldn’t say the moon is made of cheese, think of the many times in history Church leaders (not dogmatically, but still) denied basic laws of physics in the name of faith.

Just because they will intersect doesn’t mean they use the same paths.

So You Gotta have Faith?

The more science shows me about the complexities of the world, the more wonder and awe I have for God’s creation. It is only once I delve deeper into the complex realities of our existence that I sit back, look up at the stars, and finally ask “why?”

We will never know the why, beyond what God tells us. And as much as I enjoy modern philosophy and science, there are some serious issues with those subjects when they try and over-materialize things. Marx said that God was a drug used to control people and Freud said God was merely an eternal father-figure that childish humans appealed to in times of sexual insecurity. These views have proved highly reductionistic (not all faith even involves a god-figure), but they fail to take into account the logical and historical merits that a living and active deity has. The amazing and wonderful thing about our Christian God is that He wants to have a relationship with us. Christ’s ministry demonstrated this on a level that barely any historians attempt to dispute. However, even the most hardened scientific discoveries require a leap of faith at some point. Once “sufficient evidence” has been gathered, a scientist has to accept their results as somewhat universal before moving on. Even though they understand their results may be imperfect, there is a certain level of faith they have in the data that was collected.

Soren Kierkegaard once said “The knight of faith knows it gives inspiration to surrender oneself to the universal, that it takes courage to do so, but also that there is a certain security in it, just because it is for the universal.” This reaction to the Enlightenment’s era of great doubt swung faith from a child-like idiocy to embracing what it means to be mature. Faith, above all else, makes us human. The constant desire to answer life’s unanswerable questions by appealing to a power beyond our capabilities is indeed most noble and humble. It is faith that convinces us to overcome challenges. It is faith that assures us we will be okay the next morning. It is faith that keeps the best from giving up and tells the worst of us that they can turn everything around.

“I care, therefore I am.” Martin Heidegger didn’t explicitly put it in those words, but the mentality is prominent across his work. We human beings crave answers to great questions. But more than that, we are obsessed with our relation to such answers. To be isn’t simply to exist, rather it is to engage with the world around us. In this manner, faith transcends empirical measurements of any sort to allow us to trust not just others, but God, Himself. How can I be convinced that my roommates won’t murder me in my sleep tonight (they have every reason to. I keep them up with this philosophy stuff)? I can’t. I have faith. Ordinarily, one would say that comparing our faith in friends shouldn’t be equated to our faith in God, but God has reached out to us time after time. He’s not just a first mover or holder of all principles. He wants to be friends with us. This requires faith, though. All the reason in the world cannot prove a relational God.

This is what theology should focus on: how our material life and material activities impact our transcendent relationship with God. Everything in this world is temporal. God’s grace is eternal. So, while theology should use reason, it should only do so in the context of our relationship with God. Traditionally, sin has always been associated with that which damages our relationship with God. After all, our understanding of Hell isn’t so much a place, as it is eternal separation from Him.

Alright, not like that.

So What?

Looking at the institutional Church, it is clear that many Catholic leaders do not view sin relationally. Even writing this reflection series, I’ve often been accused of breaking with magisterium, and essentially disagreeing with the Church (which I assert is untrue). Likewise, I’ve talked with friends who have been told that because they sin, they have no place in the Church and that they will be condemned to Hell unless they change. Regardless of what the person did, this merciless and arrogant method is no way to approach sin. I guarantee that addressing those who’ve sinned in a more relational manner will yield far greater results than bashing them upside the head with the Catechism. Sin is about a relationship, so let’s treat it like one.

I’d like to close with Rene Descartes, a man who dared to doubt. He is best known for his phrase “I think, therefore I am.” Descartes was not an atheist; in fact, he mentions God quite frequently in his works. What’s different with him is that he starts his work by looking at the basic material, and only after thinking about the theological implications of what he observed. When we start with the material, we start with barely anything. Life is a brand new adventure. An endless sea of discovery awaits us, as we slowly encounter waves of bigger questions. This is a basic part of testing everything, as St. Paul would say. However, the great saint also urged us to retain what is good. I would argue that we need to be very careful with what we determine is “good.” And, again, Christ may have very well told us what is good, but in the grand scheme of the universe, we still have much to know. Because of faith, we know that Christ’s goods are unmovable and permanent. They will always be true. This is comforting and scary at the same time, though. In one sense, there is no need to reinvent the wheel. But in another, we might not need wheels anymore one day. Let us tread lightly with what we claim is absolutely true, and rely on our humble observation, guided by the compass of reason, to steer us to safely in a material world.

I’d like to think that Hobbes is reason.

Summary: TLDR

Causation: The Physical and the Metaphysical

- Everything has a cause, or many causes.

- A ball rolls because I pushed it, or gravity acted upon it, or God’s transcendental laws commanded it to, etc.

- Causes can be explained by using physical and metaphysical terminology

- The physical has to do with what can be interacted with by the senses

- I pushed the ball

- The metaphysical consists of whatever goes beyond our ability to sense

- God’s laws of nature pushed the ball

- The physical has to do with what can be interacted with by the senses

The Problem with Metaphysical Causation

- For centuries in the classical and scholastic time-periods, causation was attributed to both physics and metaphysics.

- However, as time moved on, and people could understand material processes better, physical causation often replaced its metaphysical counterparts.

- Still, metaphysical causes, such as God and the soul, remained as the cause of many processes, such as moving, growing, and thinking.

- The issue is that even if God and the soul exist (which I believe to be true), saying they cause something doesn’t say so much, as they can be traced back to the cause of everything. The spiritual precedes the material, so the answer “because of the soul” can be invoked about practically anything.

- Additionally, there isn’t much use in attributing causation to God or the soul, as that looks outward, rather than inward. Because God is infinitely greater than us, we will never be able to grasp His complete essence.

- Instead, God has blessed us with reason to look inward and learn the material processes that the soul animates.

- This means that no matter how advanced and complex science gets, there is always a soul that is the root cause of everything. But by just focusing on the soul, we don’t learn much about the material processes that are animated by the soul.

The Noumenal and the Phenomenal

- Immanuel Kant developed the theory that our world is characterized by two realms of being: the noumenal and the phenomenal.

- The noumenal is reality for what it truly is. It is immovable and unchanging. Only God (or a god-like figure as Kant would say) can grasp this.

- The phenomenal is how we perceive reality. It is flawed, just as our senses are flawed.

- I argue that the noumenal is God’s perfect knowledge of the world. Unfortunately, beyond divine revelation, we cannot access such perfect ideas. Instead, we remain relegated to the phenomenal, which is material.

- While this initially seems to make us powerless, it is actually a humbling concept. No matter how much we study something, we will never have God’s perfect knowledge of it.

- Rather than look outward at the spiritual noumenal, we should instead look inward at the material phenomenal.

- By understanding ourselves, we can better learn how to function better. Remember that hundreds of years ago depression didn’t medically exist. Now our medical science is so extensive that we know exactly what parts of the body need assistance when someone suffers from mental illness.

- So, by learning more about the parts, and how to improve those parts, we learn how Christ intended His body to work.

Natural and Divine Law

- Divine Law is how God commands us to live. Divine Law is noumenal, meaning we cannot possibly understand it without God’s divine revelation.

- Because of this, God has blessed us with Natural Laws which guide the material universe. These laws remain constant throughout all of human existence and dictate how everything functions (e.g. 1+1=2).

- Natural Laws, unlike Divine Laws, are interactable without revelation. Reason enables us to recognize them. Therefore, we should study them, which requires study of the material.

- If God truly made us in His image and capable of reason, Natural Law will always match up with Divine Law. If God didn’t make this so, God would not be all loving, as an omnibenevolent God would surely give us the tools to understand our environment by studying it.

- Beyond this, we need reason to evaluate claims based on faith. Otherwise, anything a person claiming God spoke to them would be considered true.

- Again, justifying laws to govern the material universe by saying “because God said so” doesn’t say much. If we simply stop there and accept that fact, we will not learn anything more about the material processes that explain why things work the way they do.

- God’s revelation clearly is anomalous throughout history. His lack of presence illustrates His desire that we understand the material world we live in.

You Gotta Have Faith?

- Still, there are certain truths we cannot understand without Divine Law, which does surpass (but not contradict) Natural Law. God engineered our universe to behave in certain ways. By studying the universe, we can figure out how God intends us to live. We are expected to build the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth, meaning the ideal way to live exists within the material sciences God has blessed us with. However, some truths are indiscoverable without revelation, such as the Holy Trinity, the Virgin Birth, and the very idea of a relational God.

- Speaking of which, God calls us into a relationship, which involves us bridging the infinite gap between Him and us. This is impossible with reason or materialism, as no amount of reason or knowledge of the material can transcend into God’s noumenal/metaphysical/spiritual realm. We cannot have a material relationship with God. It requires faith.

- Additionally, faith enables us to ask deep unanswerable questions, such as why we exist. Faith is very unique to humanity and is an essential part of what makes us human.

- Several efforts have been made to materialize faith. This is not possible, as God has revealed Himself countless times throughout history in pursuit of a relationship with us. The very sustenance of our material world and all of its laws illustrates the existence of a loving God.

- The fact that we even seek such impossible answers demonstrates a remarkable quality of humanity that is unique to our species.

- Also, a leap of faith always must be taken when exercising reason, as we can never know anything for certainty (outside certain immutable mathematical and logical laws), but continue to build up knowledge regardless.

- Theology should not only strive to metaphysical questions, but it should also evaluate materialistic claims in the context of our relationship with God.

How this is Relevant to Theology

- For much of history, sin was viewed as any action that negatively impacts our relationship with God.

- Obviously, anytime a person’s actions do not follow Natural Law, we are not living how God intended us to. Thus, when we break Natural Law, we sin.

- However, when correcting a person who is sinning, we should not isolate or condemn them, rather we should put things in an emphasis on the impact such actions have on the person’s relationship with God.

- After all, Hell is understood by many modern theologians as the severed relationship between man and God, not an actual place.

- The fact that absolute truth exists can actually be quite scary. It means we must exercise extreme caution before deeming something to be absolutely true, as one mistake could cascade into catastrophic results down the road.

- Going back to the original problem, I say that doubt is integral towards forming our knowledge about the world, and by extension our relationship with God.

- By starting with the material and moving to the spiritual, we not only learn more about ourselves, but we open ourselves up to an eternal sea of discovery. Reason is our compass, and while we may never know things for certain, it will always point us in the right direction of God’s Natural Law.

2 Responses